Mousographs #256: „Diana bathing“

It’s a classic case of shit that happens. Actaeon’s initial idea is to just walk his dog around the block when he hears a splashing sound and unexpectedly beholds Diana and her nymphs bathing in a plate of pea soup, all of them stark naked. Oops!

Sorry, ladies, no offense intended, have a nice day. The gentleman bows and quickly retires. But this is not a proper way of relating to a goddess, and Diana will have none of your civilized bullshit.

In classical literature, the goddess of the hunt, known to the Romans as Diana and to the Greeks as Artemis, is described as „high-necked“, which means she won‘t let you see a square inch of bare flesh from anywhere between her neck and knees, let alone the faintest hint of a cleavage. Although she is known for wearing a short skirt which no lady of rank would normally be seen in, the purpose is strictly for better progress in the thicket of the forest. Diana is chaste, and so is everybody else in her gang. If they’re not, there’s trouble, as the nymph Callisto can tell you: It wasn’t her fault she got pregnant, because Jupiter raped her. But Madam shows no mercy and turns the poor thing into a bear anyway.

Actaeon is in a bad fix. He’s as innocent as Callisto was. Quite frankly, Diana could have had the decency of putting up a sign: „Caution, Goddess bathing! Trespassers will be transformed or killed or both.“ Because how on earth should Actaeon know that the next corner will have him run into an improvised pea soup peep-show?

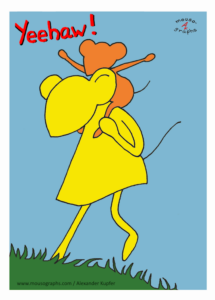

Nothing doing. Her bow and arrows being out of reach, Diana splashes Actaeon with her bathing water which makes antlers grow from his skull and soon turns the complete guy into a stag. As a result, his dogs – the legend has more than just one of them – fail to recognize their master, chasing him through the forest and mangling him to death while Diana, the party pooper, is happy again.

Since the Renaissance, bathing goddesses and nymphs have been a popular motif in art history. There is no need to speculate as to why this is the case. The trick is that although they look like naked women, it’s not what they are. They are mythological creatures, and the assumption is that mythological breasts and bottoms are different from those of humans. Mythological nudity is not offensive – as long as the mythological reference is obvious. You step closer, examine the details and praise the artist’s delicate brushwork. Manet’s “Lunch on the Grass” (1863), however, was a scandal because the painting shows naked ladies in the company of two gentlemen who are dressed in contemporary suits, thus preventing the viewer from using the mythology trick as an excuse for his or her uninhibited attention.

Why is it that nudity is so offensive when it should be the most natural thing in the world? Perhaps Diana is so angry because Actaion saw her divine problem areas, which Rembrandt depicted with impunity in a sketch in 1631. The bare flesh is the truth beneath the fantastic narratives of our clothing; it seems to be woven from a coarser fiber than velvet and silk. Those who see us naked, without cummerbunds, corsets and push-up bras, recognize us for what we are and will no longer be fooled by the augmented reality of our textile alter egos. This is, well, sub-optimal. Because each of us wants to be a story that is never finished, a narrative that keeps gripping our minds, a book that won’t be closed and put back on the shelf. This is why we go shopping – it serves the purpose of constantly reinventing ourselves by buying new clothes.

In the first place, however, nudity is a problem because it has a way of inspiring sexual fantasies or desires in the spectator. Men are pigs, but so are women. Put something on, so we can stop drooling and being distracted from our tax declarations. The public taboo on nudity becomes a distinctive feature of what we call culture, it proves that we are able to control our sex drive. Well, mostly, sometimes.

But this is not where the story ends because covering our nakedness comes along with a boosted imagination. The cleavage is invented, the slit dress, the mankini. There’s Marilyn and that upward breeze from a subway grate, oops. Now you see it, now you don’t. The flesh turns into a matter of speculation. A famous literary example can be found in Chapter 13 of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses (1922), the scene is Dublin’s Sandycove Beach on the evening of June 16th, 1904: While the crowd is looking up to the sky and admiring the fireworks, the novel’s main character Leopold Bloom enjoys a spectacle which is different but also gratifying as Gerty MacDowell playfully decides to let him have a peek up her skirts. Unlike Diana, present-day authorities have no way of turning perpetrators into stags, but British and American censorship boards were quick to ban the novel for its alleged obscenity, thus crowning it with a modern pair of antlers.

Mousographs #256: „Diana im Bade“

Aktaion ist ein Pechvogel. Eigentlich will er nur mal schnell mit dem Hund um den Block. Doch dann hört er ein Plätschern und erblickt ganz unerwartet Diana und ihre Nymphen, die in einem Teller mit Erbsensuppe baden, splitterfasernackt. Oha!

Natürlich kann so was schon mal passieren: Sorry, die Damen, nichts für ungut. Schnelle Verbeugung, dann sucht man das Weite. Aber so geht das nicht bei Göttinnen, man ist ja nicht auf dem Rummelplatz.

In der klassischen Literatur ist die Göttin der Jagd, die von den Römern Diana und von den Griechen Artemis genannt wird, als die „Hochgeschürzte“ bekannt. Zwar trägt sie ein kurzes Röckchen, in dem sich normalerweise keine Dame von Stand blicken ließe, aber das ist nur dem Zweck geschuldet, im Dickicht der Wälder schneller voranzukommen. Diana ist keusch, und alle Nymphen ihres Gefolges sind es auch. Wenn nicht, gibt es Ärger, wovon die Nymphe Kallisto ein Lied singen kann: Eigentlich war sie untadelig, und dass sie trotzdem schwanger wurde, ist nur der Vergewaltigung durch Jupiter geschuldet. Aber Madame kennt kein Erbarmen und verwandelt die Arme trotzdem in eine Bärin.

Die Sache mit Aktaion ist ein Betriebsunfall. Der junge Mann ist genauso unschuldig wie Kallisto. Vielleicht hätte Diana ein Schild aufstellen sollen: „Achtung, badende Göttin! Kein Zutritt!“ Hat sie aber nicht. Und so stolpert der Ahnungslose in seine erste göttliche Peep-Show hinein, die zugleich auch seine letzte ist.

Diana, die Pfeil und Bogen gerade nicht zur Hand hat, bespritzt ihn mit dem Badewasser, woraufhin ihm ein Geweih wächst und der ganze Kerl sich in einen Hirsch verwandelt. Dass die Hunde – in der Sage sind es mehrere – ihren Herrn nicht mehr erkennen, den zum Hirsch Gewordenen durch den Wald hetzen und schließlich zerfleischen, macht die Sache nicht besser. Aber Diana, die Spaßbremse, ist wieder happy.

Seit der Renaissance sind badende Göttinnen und Nymphen in der Kunstgeschichte ein beliebtes Motiv. Man muss nicht spekulieren, warum das so ist. Der Trick: Sie sehen zwar aus wie nackte Frauen, sind aber keine. Daher gilt die pralle Blöße von vorne und von hinten als kultiviert und nicht als anstößig – solange der mythologische Bezug erkennbar ist. Man tritt näher heran, betrachtet gründlich alle Details und lobt den feinen Pinselstrich. Manets „Frühstück im Grünen“

(1863) ist dagegen ein Skandal, weil sich zwischen den nackten Damen zwei Herren in zeitgenössischen Anzügen lümmeln und damit ganz bewusst die Illusion zerstören, es könnte sich um mythologische Wesen handeln.

Woran liegt es, dass die Nacktheit so problematisch ist, wo sie doch eigentlich das Natürlichste auf der Welt sein sollte? Vielleicht ist Diana so erzürnt, weil Aktaion ihre göttlichen Problemzonen erblickte, die Rembrandt 1631 in einer Skizze ganz ungestraft darstellt. Die nackte Haut ist die Wahrheit, die sich unter den fantastischen Narrativen unserer Kleidung verbirg, sie erscheint uns aus einer gröberen Faser gewebt als Samt und Seide. Wer uns nackt erblickt, ganz ohne Kummerbund, Korsett und Push-up-BH, erkennt uns als das, was wir sind und nicht mehr als das, was wir sein möchten. Das ist, nun ja, sub-optimal. Weil jeder von uns eine Geschichte sein will, die nie zu Ende erzählt ist und immer spannend bleiben soll. Darum geht man shoppen – es dient dem Zweck, sich mit dem Erwerb neuer Kleidung immer wieder neu zu erfinden.

Natürlich ist das Nackte auch und wohl an erster Stelle aus einem anderen Grund problematisch. Weil es Hintergedanken und sexuelle Begierden erzeugt. Männer sind Schweine, Frauen aber auch. Hechel, sabber. So kann man nicht arbeiten, zieh dir was über. Die öffentliche Tabuisierung der Nacktheit wird zum Inbegriff der Kultur, ein Beweis, dass wir in der Lage sind, unsere Triebe zu beherrschen. Also meistens, manchmal.

Doch die Verhüllung des nackten Fleisches hat auch ihre Tücken, denn sie nährt die Fantasie. Das Dekolleté wird erfunden, der Schlitz im Kleid, der Mankini. Ab und zu verrutscht ein Träger oder es kommt ein unerwarteter Windstoß, huch. Kopfkino. Ein berühmtes literarisches Beispiel dafür ist auf den Abend des 16. Juni 1904 datiert: Während die Menschen am Strand von Sandycove ein Feuerwerk bestaunen, hat die Romanfigur Leopold Bloom durch den unverhofften Blick unter Gerty MacDowells gehobene Röcke ein ganz anderes explosives Erlebnis. Nachzulesen im 13. Kapitel von James Joyces Roman Ulysses, der zwischen 1918 und 1920 auszugsweise in einer Zeitschrift veröffentlicht wurde, 1922 dann erstmals in Buchform. Natürlich wird in unserer aufgeklärten Zeit niemand mehr in Hirsche verwandelt, aber die Zensurbehörden sorgten für ein rasches Verbot des Buches und setzten ihm damit zumindest ein symbolisches Geweih auf.

Cute, it takes gods and goddesses to teach morals to upstart humans, serves them right