Mousographs - Behind the Scenes

About me

Hi, my name is Alexander Kupfer, I’m the Mousographs guy.

I was born in Bonn, Germany, and this is were I live today, right next to the beautiful Rhine.

Five years of my childhood were spent in Brussels, Belgium, a hotspot for comics. There were many visits to galleries and museums and uncounted rambles with my toy rifle in the wild spots which the urban landscape of Brussels had at the time. I think my art owes much to these precious early experiences which were packed with adventure and imagination.

Back in Germany, I finished school and studied at universities in Bonn, Swansea, Heidelberg, and Düsseldorf, finally completing my M.A. and PhD. Since then, next to my bread-earning job as a project manager in the field of international higher education, I have published several works of fiction and non-fiction (German and English; if you’re interested, see my Amazon author page). In 2020, I also started circulating my artwork.

Art Prizes and Honors:

2021:

iJungle Illustration Awards (Portugal)

Luxembourg Art Prize (Luxemburg, Certificate of Artistic Achievement)

2022:

iJungle Illustration Awards (Portugal)

2023:

Embracing Our Differences (USA)

35th Olense Kartoenale (Belgium)

6th Gold Panda International Cartoon and Illustration Competition (China)

2024:

H-Team International Comics Competition (Germany)

9th Premio Internazionale di Satira e Umorismo “Giuseppe Novello” (Italy)

Some of my Mousographs are also published at Medibang Art Street (Japan).

Scenes from the Lives of Fish

Drawing has always been my passion; give me a piece of paper and a sharpened pencil, and I won’t be able to resist the temptation. Writing is a younger passion; it came to me in my late teens when I drew my first cartoons and wrote a story to put them in. It circulated at school, and the girls loved it!

After this first experience, writing became my new passion. Writing is cool, you can sit in a café like James Joyce and scribble your brilliant thoughts on a sheet of paper, sipping your cappuccino and almost bursting with the joy of creation that fills your mind.

Much later, I was working on a novel which is set in the future when the animals take over the abandoned human civilization, getting the gist of it and trying hard not to make the same mistakes. At one point I thought it might be a good idea to have some illustrations. So, here’s one of my characters: Don Mascara, an old rabbit mafioso. The drawing gave rise to a series of acrylic paint pictures which was called “Scenes from the Lives of Fish”.

Started in late 2019, this series has turned into a project for printed publication. In 2021, some of the paintings were honored with an iJungle Illustration Award and printed in the “Annual eBook of the 2021 iJungle Award Winners”. In the same year, the jury of the Luxembourg Art Prize were so kind to award a “Certificate of Artistic Achievement”.

Mousographs

One of the paintings for „Scenes from the Lives of Fish“ was a thoughtful bear who sits in an armchair, obviously yearning for peace of mind when there is none. To illustrate the bear’s restless thinking, I painted the multitude of his thoughts as a crowd of colourful mice swarming all about him, sitting on his head and body and definitely not giving peace a chance.

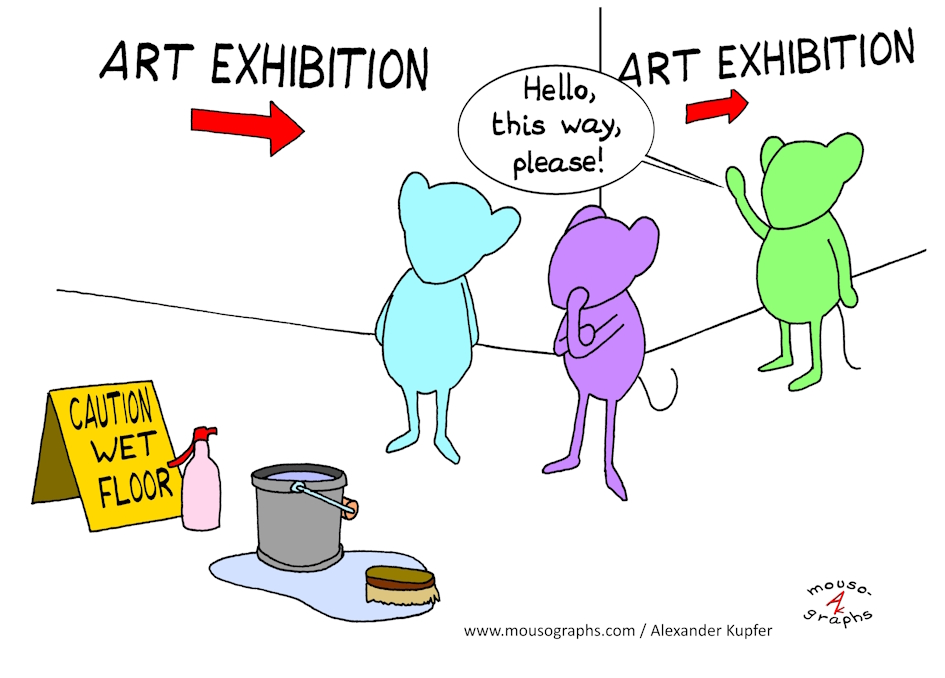

It turned out that the mice were not satisfied with their role, they wanted more. This is how the „Mousographs“ series started, which is very different from the previous project. To begin with, these mice are hyperactive and won’t wait to be provided with detailed features and environments, they don’t even want faces, or fingers and toes. To my surprise, I found that drawing their movements was absolutely sufficient to express their moods and the character of their social interaction. Like minimal art, comics, graffiti, or emojis, they convey their messages in a jiffy.

Despite so much economy, or maybe just because of it, much attention was necessary to orchestrate the correspondence of lines and colors and the creation of a sparse but credible space of action. Like a good algorhythm, “Mousographs” are simple on the surface and easy to use, because the underlying design isn’t simple at all. In the creative process, they start out with a minute of happy pencil sketching which is followed by tough hours of turning them into a message that hits your mind like lightning – because if it doesn’t, I know you will be miles away before I get it right.

In a world whose complexities seem to be getting out of hand, simplicity is what we’re yearning for. But unlike politicians who often like to cross their rivers by jumping from one stone of their limited understanding to the next and hardly ever bother to get a picture of the whole, artists will not achieve simplicity by ignoring the details.

On the contrary, they need to know the details before they can strip them down to their essentials, like e.g. a rose petal on a subway floor which may fill us with awe. They need to figure out their melting processes, and they need to invest the scruffy results with an emotional potential so that the minds of the viewers can make them shine.

So, why shouldn’t humor be included in the artist’s portfolio of emotions? In the face of things looming large – climate crimes, war crimes, religious crimes, crimes against human dignity and self-sustainability, crimes of economy and greed, crimes against the blessings of diversity, crimes of bureaucracy, crimes against freedom, or crimes against love – I believe we need it more than ever: Humor, it’s essential. If we lose it, we lose everything. This is, more or less, what my „Mousographs“ are about.

In 2022, some of my “Mousographs” were honored with an iJungle Illustration Award and printed in the “Annual eBook of the 2022 iJungle Award Winners“.

In 2023, Mousographs #209 “Colors matter” was selected along with 49 works by other artists from a total of 16,600 international submissions to take part in the 2024 exhibition “Embracing Our Differences” in Florida / USA. In the same year, the 35th Olense Kartoenale competition (Belgium) selected Mousographs #118 for its annual exhibition and printed catalogue (which is also avalaible on Youtube, you will find my work at 12:02). The work was appreciated as a contribution for the competition’s Amnesty International theme “Everyone has a right to a suitable home”.

My Concept of Art

Some time ago, the owner of a local art gallery was kind enough to accept some sample postcards of my Mousographs series for sale on her premises. She liked them a lot, yet she pointed out that these pictures were not “art” but just “illustrations”. She would place them on a rack by the door but certainly not even dream of putting them on her walls. To me, the rack by the door seemed just fine, but her distinction stayed on my mind, so let me use this space to give you my five cents about „art“.

In my view, art can be anything. It doesn’t need to be made of marble, and it certainly doesn’t need to be expensive. On the contrary, I find that the price of a thing has little to say about its value as a work of art. I also find that humor is still very much excluded from the common ideas about art, because the assumption is that it wasn’t “serious”. To which I reply: Oh no, Madam, Sir, humor is a top-serious business! Do not despise it as something low, because we need it as much as the air that we breathe. It’s at the core of what we are and what we might be. If you don’t want it, you don’t want humanity.

So what are the distinctive features of art? Of course, the libraries are filled with many volumes that try to answer this question, and I don’t want to put up another volume. Just a few remarks.

From my experience, art speaks to the recipient in two ways. One is what you may call craftsmanship: a whalebone may be admirably carved, a stone perfectly shaped into something new, the colors on a canvas may be arranged in such a way as to produce a most stunning effect. Good craftsmanship is a great thing to behold, and I will never understand how on earth Michelangelo could turn a simple block of stone into something so beautiful as his Pietà. Seeing what wonders the hands of man can perform is always a gratifying experience.

The second line of communication between a work of art and its recipient is, however, much more complex. It is based on a lie, and this lie will only work if we cooperate and are ready to be betrayed. Remember René Magritte’s „Ceci n’est pas une pipe“: The picture of a pipe is not a pipe, because you cannot use it to smoke your tobacco. The picture makes you believe that the pipe was a pipe, although in fact it isn’t; you’re truly just looking at a certain amount of paint on a piece of canvas.

Yet, the lie is much deeper than that. It doesn’t stop with making you believe that the representation of a thing was the thing itself, but it goes on to make you believe that you, the viewer, were a part of it. Talking to you, relating, drawing you into the ensemble of its suggestions, making love to you or hurting your feelings, works of art grip your mind and soul. Well, they don’t, of course, being just a concoction of dead materials, but you think they do.

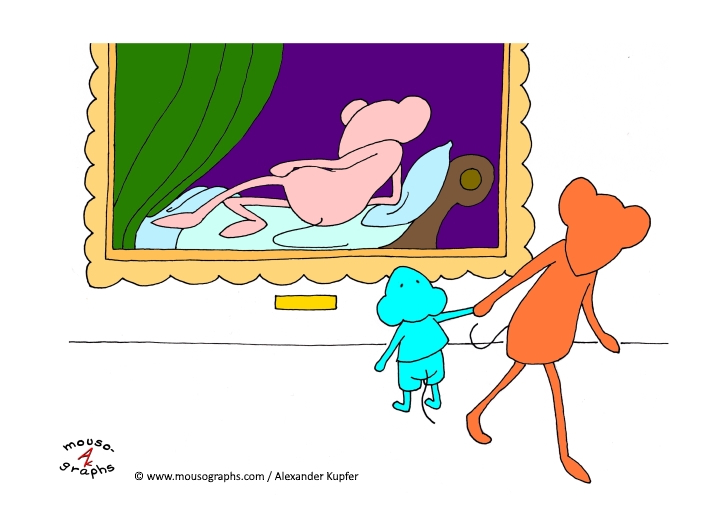

This is also true of the “objet trouvé” or “ready-made” concept of art which relies on presenting common objects in an uncommon environment, thus investing them with a (new) meaning. Take Marcel Duchamp’s notorious “Fountain” (1917), which is, in fact, a regular urinal like so many others you could have bought at any odd plumber’s store of the time. Yet, it is far from being regular. It must be, because it’s exhibited in a museum! And it is definitely not meant to be used like any other urinal.

Placed in this unusual environment, it has turned into something which is very different from what it used to be in its prior location. Like a caterpillar turned into a butterfly, it sits on the floor to be looked at, commanding your attention, appealing to your emotions, making you think. Here, the lie consists in the fact that the suggested metamorphosis never happened – the caterpillar, to be sure, is still a caterpillar, and it will never be anything else. Like it or not, but once again, accepting the lie, it’s your mind which turns that thing into art.

For this reason, a work of art can only be a work of art, if there is at least one person looking at it. At night, when the doors of the Louvre are closed, all the splendid works in the galleries lose their Cinderella spells, and they cease to be art, the carriage changing back into the pumpkin which it originally was. But as soon as the doors open again and people flock in to look at the exhibits, the magic is back.

In other words: Art without a beholder is nothing, it doesn’t even exist. It’s the eye and mind of the beholder, his or her senses, his or her soul, which turn a heap of dead matter into a living thing. Calculating this relation between a work and its recipient, devising the traps in which you will get entangled, luring you back and back again and making you see something new at each of your visits – this is what characterizes art more than anything else; it stays relevant, it doesn’t fade away, in fact I can think of nothing, except religion, that would bring us closer to our dream of immortality.

So, do I say my mousographs are art? Of course I do, because for me they are full of magic.

But what about you? Look at these pictures and find out whether or not they seem to do something to you. If they dont, it can’t be helped, but I hope they will. Maybe not by placing the Philosopher’s Stone in your hands or yielding tremendous insights into the meanings of life, but by making you think what you wouldn’t have thought otherwise, or by making you find something familiar in a mirror of your vision, or simply by making you feel good and putting that smile on your face.